Concept: Should You Switch?

Information Asymmetry & The cost of switching

In deal or no deal.

Would you switch boxes at the end?

For anyone unaware of the premise of the show, here’s a quick summary;

At the end, presuming the player gets there before making a “deal”, they get the offer to switch with the last remaining box (with the one they choose/assigned at the very start of the show).

If you were the contestant, would you switch boxes?

If you said yes and you think you know where I was going with this, it might not be the case.

If you said no, then this is probably due to one of three reasons, that might have worked in your favour in this particular situation:

You don’t understand shit about maths and probability.

Loss aversion.

Endowment Effect.

I want to discuss a few of these and get into some more real world examples about switching, the costs associated, biases against it and some other concepts around why its so tough to switch.

Starting with the most famous example of a similar problem where these ideas were first popularized.

The Monty Hall Problem

The Monty Hall Show: "Let's Make a Deal" was a game show hosted by Monty Hall where contestants chose between 3 doors, boxes, or curtains to win prizes, often involving dramatic reveals and psychological pressure.

The Monty Hall Problem: You choose one of three doors (one has a car, two have goats). After you pick, Monty opens one of the remaining doors to reveal a goat (every time), then offers you the chance to switch your choice.

The Correct Solution: You should always switch - it doubles your odds from 1/3 to 2/3. When you first picked, you had a 1/3 chance of being right, meaning there was a 2/3 chance the car was behind one of the other two doors. When Monty eliminates one wrong door, that entire 2/3 probability concentrates on the remaining unchosen door.

The key is that the host always opens a door with a goat behind, meaning he knows which door the car is behind.

So people assume this is a simple maths problem.

66.6% > 33.3%, but that’s not the concept I wanted to discuss.

The Monty Hall problem is actually not a maths problem at all.

It’s not a probability puzzle either.

I was going to write about how deal or no deal is a bigger version of the Monty Hall problem as an intro to this post, and from there go into real world switching situations.

But that’s actually incorrect.

It’s actually not even close to the same thing.

Because the Monty Hall problem is not stats or maths or probability.

It’s a problem about decision making and specifically something that I’ll call information asymmetry.

It’s masked as a probability problem because the host has inside knowledge!

He knows where the prize or car is, and hence to keep the show going he will always choose a door with a goat, revealing a probability weakness.

Obviously because it’s a gameshow we know he’s not going to go AWOL one day and mix up whether he shows a car or a goat first.

Whereas in the deal or no deal gameshow, the host (as far as I know) doesn’t know where the prizes are, so it is just pure chance.

So its a completely different concept.

So in answer to the very first question/title “should you switch?” —> In deal or no deal, the answer is: it doesn’t matter.

But in the real world, it actually does.

In general, yes you should switch more, because you have information asymmetry, both about yourself (internal) and about opportunities that exist (external).

They are also vastly larger than 66% to 33% probabilities.

They are even more asymmetrical bets.

Take a simple tweaked example question.

What’s the likelihood that the first job or industry you got into was the best one for you?

What about the third, or the fifth, or even the 10th?

Probably a pretty low probability that it was THE BEST.

But how many positions have you actually tried, or businesses or hobbies or projects or cities to live in….?

Usually very little.

Also these are usually the things that really matter.

That’s because it’s simply not that easy to get up and change industries or jobs or cities.

Which is why so many people don’t make this switch to just try something new.

It’s like being the host and being able to open doors/boxes but choosing not to, choosing to just stick with the one you have, making your odds so much worse.

From a human perspective we know why we do this.

Starting from scratch is just really f*cking hard.

It’s just we hate starting again.

It feels like losing or going backwards.

It’s sunk cost all over again.

It’s ego as well.

This whole idea contains so many human biases that its tough to breakdown into parts.

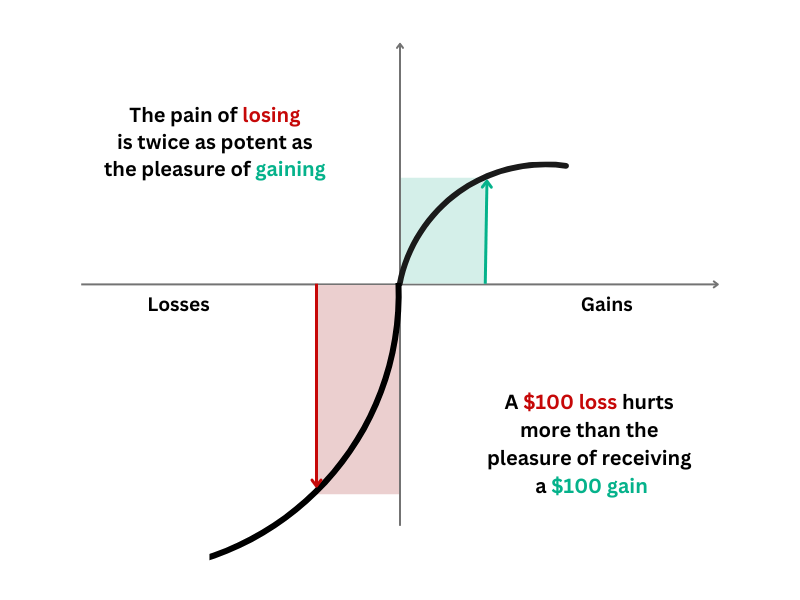

The biggest player though, in my opinion, is loss aversion.

As human’s we hate losing more than we like winning, by almost 2:1 according to all the Kahneman and Tversky research.

This just makes doing anything that has a 50/50 shot, effectively not worth it (from a mental standpoint).

Another reason why betting is tough as an industry, having one positive day and one negative day for the same amount feels worse than it should.

Another common bias in this same sphere is the endowment effect.

Essentially meaning that between these 2 biases, something you have (that you risk losing) vs something that you don’t have or know, that may or may not be better is a really tough trade off to make, and hence we don’t risk it.

Let’s say you have a 6/10 life in your current city.

Moving all that up and trying to build an 9 or 10/10 life in a new city, regardless of all the associated hassles of moving that life, makes this decision incredibly difficult to do, because in your head it could be even worse than a 6!

Information Asymmetry

I’m going to do an entire post on information asymmetry in the future as it’s a very interesting concept to me, so I’ll keep it brief, but in this switching sense there’s some obvious examples that relate back to human nature, biases and why switching is so tough.

Probably evolution’s fault thinking about it.

If we stick in a tribe with everyone we know we’re (probably) not going to get murdered or eaten or freeze to death.

But if we look for better options and leave the tribe, that likelihood probably increases 10,000%.

So why risk sacrificing a 6/10 life for a 9/10 potential one?

I think that, in essence is the issue.

If we had the information available to reduce that unknown gap, then it would make the switching way easier to do.

But more on information asymmetry in the future.

Switching In Business

Everyone who knows me, knows I always bang on about the concept of just doing one thing really really well.

Don’t start multiple projects, because you will suck at all of them.

Dilution of effort / resources.

The sum of its parts is not equal to the whole in this case.

This is advice I wish I took years ago, as by not doing this, I’ve had far more issues and less success, making it easily my biggest (of many) business mistakes.

It’s not to say you have to do one thing forever.

Instead it’s about going all in on one thing at a time.

You’ll make far more progress doing something 10 hours a day for 3 months than 10 minutes a day for a decade.

You also build momentum and success, which will build confidence in the flywheel.

There’s obviously exceptions.

You can’t lift weights for 10 hours a day for 6 months, but for skill/business/personal growth related goals, it’s a rule that applies most of the time.

The reason why doing one thing at a time, the sprint then rest mentality, is a good approach is that resources and energy only go so far, especially at the extremes.

Michael Jordan, arguably the goat of goats, literally tried competing in a second sport and failed miserably.

But choosing the first thing you do and aiming for mastery of that can also be a pretty bad decision.

The small-business-restaurant-owner who works 90 hours a week and earns 60k a year is not working any less hard than the founder of another “small business” with 9 employees that does 10 million a year.

They are just different.

They are just working on different things with different upsides and importantly different leverage.

Which is another post for the future.

This idea of switching, both intra-day (task switching literally makes you less effective both in the short and long term) — AKA do one thing really well.

As well as switching in the macro-sense — “I have this semi-successful business/project/job that is fine and if I grind I can make a lot of money…. But if I start again I’ll have to go backwards”.

AKA — Less money, less short term success, more chance of failure, ego bruising etc.

So in short, it depends.

Which is always a boring cop-out answer whenever someone says this.

So instead, some ideas and questions to think about in regards to this.

One question of which I think nails it, that if you are asking yourself more than once a quarter, then you should seriously think about switching.

Versions of; “Why am I here”, “I dislike this” “would I be better in/at X”, Googling other job ventures, proactively looking into other cities etc.

In this case the signal is super clear, it’s just the hassle around action.

The pain of switching is something we all know about, the same reason we stay in “fine” accommodation because the week of moving is such a pain in the ass.

Or why we stay in a comfortable city or location rather than something that would be great if we made it so.

You don’t have to switch “EXTREME”

You don’t need to switch from a restaurant owner to a day trader.

But if you feel like you perform extremely well in your industry but it’s seen as a commodity, going “up” the chain may be worthwhile.

There’s steps in-between, skills to learn and information to acquire that benefit you both in the short-term and longer-term.

Regret Minimization

When researching this idea, one concept that came up alot was the "Regret Minimization at 80" framework.

A framework popularized by Jeff Bezos.

Tweaked to our example would be something along the lines of “Will you regret not trying the switch more than you'll regret the short-term setback of switching?”

Most people over-weigh short-term pain and under-weigh long-term regret.

It’s a similar idea to delayed gratification.

The difference being you don’t actually know for sure if it will be better.

Unlike many delayed gratification ideas, working out, saving money, eating well, these are all pretty much definitely going to make future-you better than present-you.

Moving cities or jobs or businesses might not.

It genuinely could just be a shit idea or shit execution.

I also think it’s even more difficult to come at this concept if you are already doing “okay” or even “good” - because giving up that completely (remember just choose one thing) to go after something great is more difficult than starting with nothing and going after great.

If you have a 1/10 life and you are trying to get to a 9/10 life, if it doesn’t work out (after say a year) you’ll have a 1/10 life again. If it does, then jumping “8 points” is worth the risk. You literally have nothing to lose in the first situation.

If you have a 6/10, you might drop to a 4/10 for a while in search for the 9/10.

This is something that I think about personally alot, I think I have a great life, but I want to get to epic. So going from 8 or 9/10 to 10/10, to do that, I have to risk going down first.

Of course add some concrete blocks, never risk the non-negotiables.

But after that, switch more.

Risk more.

It’s not even a “try more new stuff” idea.

It’s literally a switch-more.

Go all-in on something important more often.

Obviously, do this in a smart way, but just remember we’re all basically programmed to hate switching big things in our life.

So if you’ve considered it, you should probably do it.

Going from high paying, dull, corporate job or semi-successful client facing business where you might make 100-200k a year, to switch to something you’ve never done (all in) before, going to literal 0 for X amount of time, it’s scary and tough both in practice and just mentally.

This is made even more difficult as you are not vindicated straight away.

It’s not like the guy that quit the job or quit the business to do something else gets vindicated on day one, usually not even year one.

It’s years before they or anyone else can look back and realistically say, I’m glad I switched. Or get a positive response around “that was a good decision”.

In the practical sense many people say “I’ll start this alongside <current thing> and once it reaches <X amount> (almost always what they earn now) I’ll quit the business/job etc”.

Side-bar: This is not about “do what you love” - there’s been tons of research around that not being the best advice, this is more about “do what you want to do”.

If you want to start a trash collection business because a.) they all suck, b.) you have the skills for it and c.) you could make tons of money and give your family/friends a better life… That’s probably something you’d want to do.

It’s also probably not your passion.

Still Not sure whether to switch?

Some final ideas and questions to think about.

Ignoring the obvious ideas around; opportunity cost, time value, pros/cons etc, here’s 3 final unique ideas:

What option will give you a better social life? — Both by doing the thing and also have more (or less) time to spend socially. Removing money entirely what option is preferable (hidden costs in life).

Energy - what activities give you energy vs drain it? — Which will you do more of in each situation? Energy is finite. Sometimes switching isn't about money, it's about not dying at 50 from stress (or boredom).

Depth & Options - what gives you even more options in the future? — Are I in a dying industry? Do I think the people around my business will grow? Are the skills I learn in the next stage (of progression/business) even useful?

Some ideas to think about.

Cheers.

Tom.